Discoveries of a translator

In 1992, when I worked on the Dutch translation of The English Patient, little was known - outside Hungary, and apart from a small circle of experts on the North-African desert - about the historical figure on which the protagonist of the novel was based: Count László Almásy. That changed dramatically after the film version came out in 1996. Biographical articles appeared in newspapers and magazines, in Hungary a society was founded for the study of the life of the desert explorer, and in 1997 a German documentary, entitled “Through Africa by Automobile”, was made with original footings of his desert journeys.

But in 1992, the only place where I could find his name was the catalog of the Royal Dutch Library in The Hague, which had a German translation, published in 1943, of his book Unknown Sahara (Az ismeretlen Szahara). I drove to The Hague to consult it, and the trip proved worth while. Not only was it a fascinating book, it also contained magnificent illustrations, among which two color prints of rock drawings in what Ondaatje called the “Cave of Swimmers”. For those who haven't read the book: the “Cave of Swimmers” is a cave in the middle of the bone-dry Sahara with prehistoric drawings of obviously diving and swimming people. This is an indication that there probably was a lake when the drawings were made, and that the Sahara therefore wasn't a desert in that time. In the novel it is put like this:

In Wadi Sura I saw caves whose walls were covered with paintings of swimmers. Here there had been a lake. I could draw its shape on a wall for them. I could lead them to its edge, six thousand years ago.

The drawings are astonishingly gracious and simple, and totally different from the European prehistoric drawing we know from Southern France and Northern Spain. They have an abstract quality which makes them almost modern, they remind one of drawings by Paul Klee. The picture below, showing the “swimmers”, is the first color illustration in the book; the print of the hand is probably made by one of the prehistoric artists.

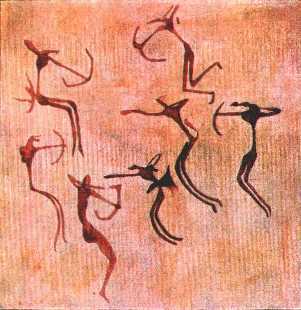

Even more beautiful – slender, gracious – are the “archers” of the second color illustration:

It is somewhat a mystery to me why these magnificent drawings have never been used to illustrate Ondaatje's novel - on the book cover, for instance - or why they haven't become world famous after the success of the film. They would have been perfect material for the film, in their original form, but what we see - in the introductory shots - is only an artist's impression of the rock drawings, not the rock drawings themselves.

Wadi Sura (or “Wadi Sora”), the location of the cave, is a dry river bed in the Gilf Kebir, a mountainous area in the south-western corner of Egypt, in the Libian Desert. In his book, Almásy writes extensively about the Gilf and the circumstances which led to its discovery, but Ondaatje probably never consulted the book, because he doesn't mention it in the acknowledgements - and it wasn't translated into English. The description of the discovery, voiced by “The English Patient” in the novel - see the chapter “South Cairo 1930-1938” - is not due to Almásy, but to two other desert explorers: his friend and expedition companion Dr. Richard A. Bermann (mentioned by name in the novel) and Wing-Commander H.W.G.J. Penderel.

Their accounts of the expeditions are recorded in The Geographical Journal, published by the British Geographical Society. Ondaatje refers explicitly to this journal. He says he quoted a passage from one of the articles and has drawn from the journal “to evoke the desert of the 1930s”. But still, I was surprised to see how much he actually took from the journal which didn't end up in italics or between quotation marks in the book. Take the introductory quote to the novel:

Most of you, I am sure, remember the tragic circumstances of the death of Geoffrey Clifton at Gilf Kebir, followed later by the disappearance of his wife, Katharine Clifton, which took place during the 1939 desert expedition in search of Zerzura. I cannot begin this meeting tonight without referring very sympathetically to those tragic occurrences. The lecture this evening...

|

The date “194-” Ondaatje needed for the chronology of his story, but a statement of this nature will not be found in the annals of the 1940s.

In the proceedings of the meeting of January 8, 1934, however, I found this:

Most of you, I am sure, remember the tragic circumstances of the death of Sir Robert Clayton-East-Clayton, followed later by the death of Lady Clayton-East-Clayton... I cannot call upon the readers of the paper to begin their address without referring, very sympathetically, to those tragic occurrences (Geographical Journal, June 1934, pp. 463-464)

In the “South Cairo” chapter, the English patient talks of “... a snakelike mysterious old man... An old Tebu, a caravan guide by profession, speaking accented Arabic. Later Bermann says ‘like the screeching of bats’, quoting Herodotus.” The account of (the real) Richard Bermann reads: “... an old Tebu who was by profession a caravan guide: a snake-like, mysterious old man, quite black. He spoke Arabic with a strong accent... For the first time I heard that language ‘like the screeching of bats’ which Herodotus mentions.” (Geographical Journal, June 1934, p. 459.)

One page previously in the novel, an expedition is described which uses for

the first time a new invention for cars: air tires. In the novel it is put

like this: “By now we travel in A-type Ford cars with box bodies and

are using for the first time large balloon tires known as air wheels.”

I liked it, what Ondaatje had made up there, but when I read the journal,

it turned out that not one word had been invented. Wing-Commader

Penderel: “For our transport we had

selected four A-type Ford cars with box bodies... For the first time on

any desert

expedition the new enormous balloon tyres known as air wheels were tried."

(Geographical Journal, June 1934, p. 453.)

Another fascinating trail led from the chapter “In Situ” to Unexploded Bomb, a book by a British major, A.B. Hartley, who wrote a history of the English Bomb Disposal Service in World War II. Ondaatje also refers extensively to this book. He says he quoted directly from it (chapter “In Situ”) and based “some of Kirpal Singh's methods of defusing on actual techniques that Hartley records”. I was very curious to read the book, if only because the defusing methods described in the novel are sometimes pretty detailed, and I couldn't always follow them step by step.

I was lucky to find exactly one copy of the book in Holland (at the Royal Military Academy in Breda), so I didn't have to apply to a British or American library to lend me one. Reading this book also proved very worth while, and, again, it turned out that Ondaatje had invented little. The characters Lord Suffolk, and his secretary Miss Morden, plus chauffeur Mr. Harts (Fred Harts) in the “In Situ” chapter, really existed. They were called “The Holy Trinity” through the whole bomb disposal organization (Ondaatje also speaks of “the trinity”). And the accident, in which all three of them were killed at Erith, really took place. Ondaatje: “A 250-kilogram bomb erupting as Lord Suffolk attempted to dismantle it. It also killed Mr. Fred Harts and Miss Morden and four sappers Lord Suffolk was training. May 1941” Hartley: “It is sad to have to record that Lord Suffolk, his secretary, his chauffeur, an N.C.O. and four sappers were all killed at Erith in May 1941 when a 250-kg. S.C. exploded.” (p. 46).

In the next chapter, “The Holy Forrest”, a detailed description is given of a defusing method in which the fuse head is frozen with liquid oxygen to make the batteries inert, so that the head can be safely removed. First, a clay cup is moulded around the fuse head, in which liquid oxygen is poured. When a wet piece of cotton, pressed against the bomb mantle at a distance of about twelve inches from the fuse, is immediately frozen solid, the fuse is cold enough to be extracted safely.

Everything is true, word for word. Hartley: “A clay or plasticine cup would be moulded round the fuze-head and manually filled and replenished with liquid oxygen until the surrounding circle of frost, a foot in radius, had been achieved. As a test for this a piece of wet cotton must frees solidly on to the metal bomb-case at a distance of ten inches from the centre of the fuze.” (p. 147) Below is a picture of such a defusing process (p. 233).

An example of a German bomb fitted with a Y-fuze... From left to right can be seen: blanked-off fuze-head in the forward pocket; the magnetic microphone with lead to the stethoscope, and the clay cup for applying liquid oxygen to the head of the Y-fuze. |

In the “Holy Forrest” chapter, Kip has a stroke of bad luck. The fuse head breaks off and the main body of the fuse is stuck in the bomb mantle. He then starts dripping liquid oxygen on the exposed part of the fuse body and chipping away at it to get to the wires. As unlikely as it seems, this is, again, entirely based on a true event. It was a certain Major Martin who wrought this miracle. Hartley: “His audacious plan was to dribble liquid oxygen on the exposed part of the fuze, chip away the surface, dribble on some more oxygen, and so remove it bit by bit till he was able to break the contacts of the circuit... This was a most hazardous proceeding and demanded intense concentration; if his tool should penetrate only a fraction too deep it would strike the percussion-cap that flashed the gaine.” (p. 150)

And – it's getting repetitious – also the microphone in the bomb pit, which was used to keep the other members of the disposal unit informed about the proceedings of the defusing process, is historical reality. From a certain point onwards, those monologues were even recorded (on magnetic wire), for analysis after the event, in case something went wrong. Hartley's book contains a transcription of one of those recordings, which ends with the words: “Fuze out. Gaine off.” (p. 151) Ondaatje changed this into: “Fuze out. Gaine off. Kiss me.” (“The Holy Forrest”)

I was quite curious, by this time, to see that particular bomb with that particular fuse. I contacted the Dutch Explosives Disposal Service of the Royal Army, to ask if they had ever come across such a bomb. They had, and they could show it to me - or rather, the fuse, wich was my main purpose anyway.

I drove to their headquarters, and there it was, standing in a glass case, like a museum piece. I could take it in my hands, I could play with it to see how it worked, and I could follow the “defusing” process with my eyes, step by step.

I felt like an egyptologist who, having read about a certain Farao's artefact, finally, after years of excavating, is standing in a royal tomb, holding the very object in his hands. And that's how I put it back, like a precious piece from a lost civilization.

Copyright © 2000 Jos den Bekker.